Introduction

The geometry list file (glist) describes the geometry present in a scene. It is the newer, XML replacement for the older Object Database (ODB) file format. The goals of introducing this file to replace the ODB file were multi-fold:

-

We wanted more flexibility in instance location descriptors

-

GLIST supports geographic locations

-

-

We wanted more flexibility in instance orientations descriptors

-

The ODB format supported either Euler angles with a fixed rotation order or an explicit 4x4 affine transform that bundled location, scale and rotations.

-

-

We wanted to expand the set of internal geometry primitives (e.g. spheres, boxes, cylinders, etc.) and to support instancing of a specific primitive (which the ODB format did not support).

-

We wanted a more flexible format to add more dynamic instancing options.

|

|

Although this format is more powerful and flexible than the older Object Database (ODB) format, the GLIST format is NOT supported by either Bulldozer or the Blender plugins at this time. Hence, it is useful only for hand-crafted scenes. |

The primary component of a GLIST file is the <geometrylist>, which

describes one or more geometry objects and where they appear in the

scene (or relative to the parent geometry that inserts them). The

following example shows a simple GDB object that appears in the scene

once at a fixed (static) location and a second time using a movement

description:

<geometrylist enabled="true">

<object>

<basegeometry>

<gdb><filename>truck.gdb</filename></gdb>

</basegeometry>

<staticinstance>

<translation>

<point><x>0</x><y>0</y><z>0</z></point>

</translation>

<rotation>

<cartesiantriple><x>0</x><y>0</y><z>90</z></cartesiantriple>

</rotation>

<scale>

<cartesiantriple><x>1</x><y>1</y><z>1</z></cartesiantriple>

</scale>

</staticinstance>

<dynamicinstance>

<keyframemovement>

<filename>truck.mov</filename>

</keyframemovement>

</dynamicinstance>

</object>

<geometrylistinclude name="Cars" enabled="true">cars.glist</geometrylistinclude>

<object>

<basegeometry>

<sphere>

<matid>4</matid>

<radius>8.0</radius>

<center><point><x>0.0</x><y>0.0</y><z>0.0</z></point></center>

</sphere>

</basegeometry>

<staticinstance>

<translation>

<point><x>-12</x><y>3</y><z>4</z></point>

</translation>

<rotation units="degrees">

<cartesiantriple><x>0</x><y>0</y><z>0</z></cartesiantriple>

</rotation>

<scale>

<cartesiantriple><x>1</x><y>1</y><z>1</z></cartesiantriple>

</scale>

</staticinstance>

<dynamicinstance>

<keyframemovement>

<filename>rolling.mov</filename>

</keyframemovement>

</dynamicinstance>

<dynamicinstance>

<keyframemovement>

<filename>bouncing.mov</filename>

</keyframemovement>

</dynamicinstance>

</object>

</geometrylist>Notice that this example defines the basics of a <geometrylist>. A

<geometrylist> contains one or more <object> entries, and each <object>

entry is comprised of:

-

The "base object" that will be instanced one or more times.

-

The list of one or more instances describing where the base object will appear in the scene.

|

|

The enabled attribute allows the user to temporarily disable a

piece of geometry rather than deleting it.

|

The user can also include another geometry list by using the

<geometrylistinclude> element as shown below the first object.

|

|

You can also instance another glist or ODB (statically or dynamically), see "Instancing Another Geometry List". |

Primitive objects (analytical constructs that are mathematical surfaces other than triangles) are handled in the same way as facetized geometry — the base geometry is used to define the prototype object and instances place copies into the scene.

The user can also add point sources (see Sources)

to the scene directly from the glist rather than representing them

with a single vertex and normal in a GDB (Geometric

Database) file. In this case, the base object is a source rather

than a piece of geometry and is defined using a <basesource>

element (see the Base Sources section below).

|

|

Extended geometric sources

(i.e. pieces of geometry that are used to model

volumetric shadowing) can only be defined as an instance of a piece

of <basegeometry>, not as a <basesource>.

|

Base Geometry

This section describes the various types of base geometry that are

supported. The base geometry is described in the <basegeometry>

element.

Facetized Geometry

The primary geometry used by most users in DIRSIG are objects defined by a set of polygons or facets. DIRSIG natively supports attributed, facetized geometry in the following formats:

|

|

As of DIRSIG 2025.09, OBJ and FBX files are also loaded via the assimp library. |

There are a variety of options available for facetized geometry that are described in separate sections of this manual:

-

The (optional) generation of tangent data to support advanced mapping options.

-

The (optional) overriding of material assignments on the per-object or per-instance level.

Geometric Databases

The user can supply a DIRSIG Geometric Database file

using the <gdb> element that contains a <filename>.

The path for this file is assumed to be relative to the

geometry search path

specified in the scene file, or relative to the simulation directory

or absolute.

<basegeometry>

<gdb><filename>car.gdb</filename></gdb>

</basegeometry>|

|

This base geometry type supports the optional <temperature>

override, which will set the temperature of every facet to the

supplied value.

|

Alias/Wavefront Objects

The user can supply an Alias/Wavefront Object file using the <obj>

element that contains a <filename>.

The path for this file is assumed to be relative to the

geometry search path

specified in the scene file, or relative to the simulation directory

or absolute.

<basegeometry>

<obj><filename>car.obj</filename></obj>

</basegeometry>|

|

This base geometry type supports the optional <temperature>

override, which will set the temperature of every facet to the

supplied value.

|

MuSES Objects

DIRSIG allows the user to import geometry and temperature predictions produced by the Multi-Service Electro-optic Signature (MuSES) model produced by ThermoAnalytics, Inc. MuSES is an advanced infrared signature prediction code that can model complex targets that include active heat sources, conduction and computational fluid dynamics (CFD). At this time DIRSIG supports a basic MuSES import mechanism, which works as follows:

-

The user creates a working MuSES simulation of the object of interest.

-

The geometry of the object and the output of the MuSES simulation of that object are stored in a MuSES TDF file.

-

-

The TDF file for the MuSES simulation, containing both the geometry and the predicted temperatures (for one or more simulated times) is "imported" into the DIRSIG simulation.

-

This import process extracts the geometry and a set of temperature predictions from the MuSES TDF file.

-

-

The TDF import operation is performed during the DIRSIG initialization, and requires the user to:

-

Instruct DIRSIG how to remap MuSES materials to DIRSIG materials

-

Instruct DIRSIG which simulated time to use for the DIRSIG simulation

-

-

The imported geometry is attributed with the DIRSIG native materials (based on associations with MuSES materials) and temperatures (based on the time provided by the user).

|

|

This simple import is referred to as a level-0 integration with MuSES. In DIRSIG5, the MuSES plugin provides a more advanced level-1 integration option. |

A MuSES predicted object is imported in a similar syntax to that

used for the GDB and OBJ file, the TDF file is specified in the

<basegeometry> via the <tdf> element. This element requires 3

sub-elements:

-

The

filenameelement specifies the name of the TDF file. -

The

materialidremappingselement specifies the list of material ID mappings. -

The

resulttimestepindexelement specifies which of the temperature results contained in the TDF file to import.

<basegeometry>

<tdf>

<filename>vehicle-insight-transient.tdf</filename>

<materialidremappings>

<remap>

<tdfid>1</tdfid>

<dirsigid>50</dirsigid>

</remap>

</materialidremappings>

<resulttimestepindex>8</resulttimestepindex>

</tdf>

</basegeometry>The list of material ID remappings is composed of series remap elements

that contain MuSES and DIRSIG material ID pairs. In the example here,

the MuSES material ID 1 in the TDF file will be modeled in DIRSIG with

material ID 50.

|

|

The MuSES and DIRSIG material ID schemes are completely independent, however, if you are creating and managing both simulations then you might consider making the material IDs the same in both tools. |

If the TDF file contains multiple materials, then multiple remap elements

will need to be defined ( one for each material).

|

|

Each material utilized in the MuSES TDF file must be remapped to a valid DIRSIG material ID. |

AutoDesk FBX (DIRSIG5 only)

The major benefit of the AutoDesk FBX format is that it is binary (compared to being ASCII/Text like GDB and OBJ) and it is widely supported as a first class format on most popular 3D content generation tools. Similar to the OBJ format, FBX supports shared vertex lists, facet groupings, material definitions and assignments, texture coordinates and vertex normals. The format also supports internal hierarchies, instancing and keyframe motion, which makes it suitable for storing individual objects or entire scenes. At this time, the GLIST import support assumes that the FBX contains a single, "flat" (no hierarchy) object and ignores any motion. The material descriptions in the file will be ignored but the material assignment names will be used to associate DIRSIG materials. If you wish to re-map these material assignments to other DIRSIG materials, you can use the GLIST material overrides feature.

<basegeometry>

<fbx><filename>aircraft.fbx</filename></fbx>

</basegeometry>Open Asset Importer (DIRSIG5 only)

The Open Asset Importer (assimp) library supports a large number of commonly used 3D geometry formats. A complete lists is available here. At this time, the GLIST import support assumes that the asset contains a single, "flat" (no hierarchy) object and ignores any motion. The material descriptions in the file will be ignored but the material assignment names will be used to associate DIRSIG materials. If you wish to re-map these material assignments to other DIRSIG materials, you can use the GLIST material overrides feature.

<basegeometry>

<assimp><filename>aircraft.gltf</filename></assimp>

</basegeometry>Geometry List

The base geometry can also be another GLIST or ODB file:

<basegeometry>

<glist><filename>another.glist</filename></glist>

</basegeometry>or

<basegeometry>

<odb><filename>another.odb</filename></odb>

</basegeometry>And the user can then instance that GLIST or ODB file one or more times into the scene using the same instancing options available for other types of base geometry. This is a mechanism that can be leveraged to easily duplicate large areas of a scene.

Box

A box primitive is modeled using an axis-aligned convention which

requires that the user define two corners of the box at the minimum

and maximum points (labeled as lowerextent and upperextent,

respectively). While this results in a box that is always exactly

aligned with the axes of the local coordinate system, the box may

be rotated out of alignment using the instance transform.

In addition to the geometric definitions, the user must provide a material ID to apply to the box and has the option of giving a temperature (in degrees Kelvin).

Texture coordinates

This primitive has a built-in UV coordinate system. Each face has

UV coordinates that go from 0,0 in the lower-left to 1,1 in the

upper-right. At this time the UV coordinates do not wrap around

the box.

<basegeometry>

<box>

<matid>100</matid>

<lowerextent><point><x>-1.0</x><y>-0.5</y><z>-0.4</z></point></lowerextent>

<upperextent><point><x>1</x><y>0.5</y><z>0.2</z></point></upperextent>

<temperature>300</temperature>

</box>

</basegeometry>Cylinder

This primitive uses a analytical description of a cylinder. The circular endcaps and sides are mathematically defined and, thus, have infinite curvature.

Texture coordinates

This primitive has a built-in UV coordinate system. The sides have

UV coordinates that wrap around the cylinder. The circular endcaps

have orthogonal UV coordinates with 0.5,0,5 at the center of the

endcap.

Default

The default cylinder is vertically aligned (along the z-axis) from z = -0.5 to z = +0.5 and has a radius of 1. The only required element in the definition is the material ID associated with the geometry:

<basegeometry>

<cylinder>

<matid>100</matid>

</cylinder>

</basegeometry>Customization

In addition to transforming the cylinder with a static/dynamic instance transformation, the user can define the orientation and length of the cylinder by providing the two cap center points. The shape of the cylinder can be further modified by providing the radius and the temperature can be set in degrees Kelvin:

<basegeometry>

<cylinder>

<matid>100</matid>

<point_a><point><x>+0.7</x><y>+1</y><z>0</z></point></point_a>

<point_b><point><x>-0.7</x><y>-1</y><z>1</z></point></point_b>

<radius>0.5</radius>

<temperature>300</temperature>

</cylinder>

</basegeometry>Cap Options

Either or both of the cylinder cap may also be removed by setting the corresponding attribute to false:

<basegeometry>

<cylinder cap_a="true" cap_b="false">

<matid>100</matid>

<point_a><point><x>+0.7</x><y>+1</y><z>0</z></point></point_a>

<point_b><point><x>-0.7</x><y>-1</y><z>1</z></point></point_b>

<radius>0.5</radius>

<temperature>300</temperature>

</cylinder>

</basegeometry>

<basegeometry>

<cylinder cap_a="false" cap_b="false">

<matid>100</matid>

<point_a><point><x>+0.7</x><y>+1</y><z>0</z></point></point_a>

<point_b><point><x>-0.7</x><y>-1</y><z>1</z></point></point_b>

<radius>0.5</radius>

<temperature>300</temperature>

</cylinder>

</basegeometry>Disk

This primitive uses a analytical description of a disk (circle). The shape and extents are mathematically defined and, thus, have infinite curvature.

Texture coordinates

This primitive has a built-in UV coordinate system. The disk has

orthogonal UV coordinates with 0.5,0,5 at the center of the disk.

Default

The default disk is centered at the origin with the surface normal (facing direction) pointing up (+z). The default radius is one and the only required element is the material ID associated with the object.

|

|

The disk is a section of a plane and has no thickness. If a solid object is desired, it is recommended that the user create a very thin cylinder. |

<basegeometry>

<disk >

<matid>100</matid>

</disk>

</basegeometry>Customization

The disk can be further customized by providing a radius, a temperature, and a specific normal vector (which doesn’t need to be normalized) to determine the orientation before instance transformation:

<basegeometry>

<disk>

<matid>100</matid>

<radius>0.5</radius>

<temperature>300</temperature>

<normal><point><x>-0.7</x><y>-1</y><z>1</z></point></normal>

</disk>

</basegeometry>Curved Frustums

DIRSIG supplies a frustum object that produces a pyramidal frustum with conical corners. The frustum is characterized by sloped sides defined by bottom and top parameters. The bottom takes a width along the X and Y axes, a radius, and a center point that positions it in the scene (note that the instance transform must be used to obtain anything other than a vertically (+z) aligned frustum). The top just takes a single radius and is always centered over the bottom. The height finishes off the shape definition and the user supplies a material ID and an optional temperature.

There are a few limits to the types of objects that can be created under this scheme. The bottom radius must always be greater than or equal to the top radius and the width in both axes must be greater than or equal to twice the radius.

Texture coordinates

This primitive has a built-in UV coordinate system. The top, bottom and sides have independent UV spaces. The top and bottom feature orthogonal UV coordinates that vary as a function of XY only, and span the extents of the respective surface. The UV coordinates on the sides interpolate between the coordinates of the top and bottom surfaces.

Basic Frustum

The radii in the definition are used to connect one side of the top/bottom to the other (curving the corner):

<basegeometry>

<curvedfrustum>

<matid>100</matid>

<height>0.5</height>

<bottom>

<xwidth>1.5</xwidth>

<ywidth>1.5</ywidth>

<radius>0.5</radius>

</bottom>

<top>

<radius>0.2</radius>

</top>

</curvedfrustum>

</basegeometry>Setting the top radius to zero means that the top is a rectangle measuring the (width - (2 x radius)) in each dimension:

<basegeometry>

<curvedfrustum>

<matid>100</matid>

<height>0.5</height>

<bottom>

<xwidth>1.5</xwidth>

<ywidth>1.5</ywidth>

<radius>0.5</radius>

</bottom>

<top>

<radius>0.0</radius>

</top>

</curvedfrustum>

</basegeometry>Ramp Frustum

The <ramplength> variable can be added to change the +X side of the

curved frustum into a gradual slope or "ramp" that extents from the top

to the bottom:

ramplength values

<basegeometry>

<curvedfrustum>

<matid>100</matid>

<height>0.5</height>

<ramplength>1.5</ramplength>

<bottom>

<xwidth>1.5</xwidth>

<ywidth>1.5</ywidth>

<radius>0.5</radius>

</bottom>

<top>

<radius>0.0</radius>

</top>

</curvedfrustum>

</basegeometry>Cone

A cone can be created with this setup by setting the bottom radius equal to half the x and y widths (which should be equal for a cone). That indicates that the radius of curvature covers the entire transition from one side to the next. To complete the cone, the top radius should be set to zero, creating a point at the top:

<basegeometry>

<curvedfrustum>

<matid>100</matid>

<height>1</height>

<bottom>

<xwidth>1</xwidth>

<ywidth>1</ywidth>

<radius>0.5</radius>

</bottom>

<top>

<radius>0.0</radius>

</top>

</curvedfrustum>

</basegeometry>Approximate Box

For demonstration purposes, it is possible to approach the extreme of letting both radii be zero and build an approximate box (note that the user is advised to just use the box primitive in this case).

<basegeometry>

<curvedfrustum>

<matid>100</matid>

<height>1</height>

<bottom>

<xwidth>1</xwidth>

<ywidth>1</ywidth>

<radius>0.0</radius>

</bottom>

<top>

<radius>0.0</radius>

</top>

<temperature>300</temperature>

</curvedfrustum>

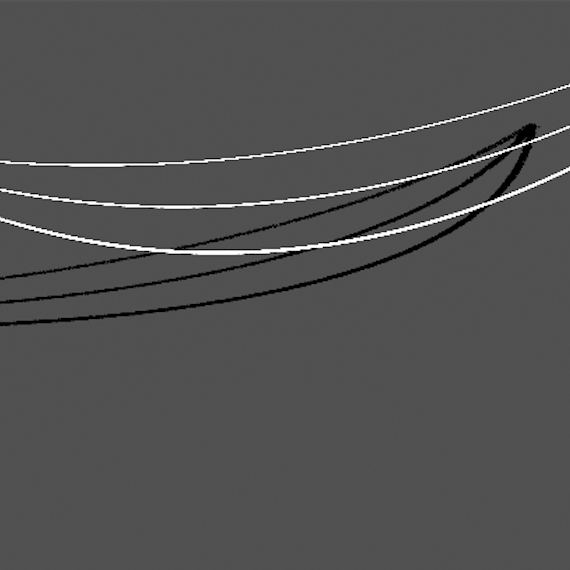

</basegeometry>Catenary Curve

A catenary curve is a hyperbolic cosine function that is a good model of objects strung between two points and sagging under their own weight. Its definition has been simplified as much as possible and requires two points ("a" and "b") and the maximum sag (in meters) between those two points. The user can also set the thickness of the material strung between the two points (assumed to be circular in cross-section) as well as the assigned material. An error will be issued if a curve cannot be generated from the parameters provided. This primitive is particularly good at representing power lines.

|

|

The sag parameter used here is not the same as the formal catenary curve sag parameter, which is harder to work with. |

Texture coordinates

This primitive has a built-in UV coordinate system. The UV coordinates have the U coordinate repeating periodically along the curve and the V coordinate wrapping around the circular cross-section of the curve.

<basegeometry>

<catenary>

<thickness>0.1</thickness>

<a><point><x>1390.57</x><y>801.823</y><z>634.064</z></point></a>

<b><point><x>1304.17</x><y>825.456</y><z>635.46</z></point></b>

<matid>301</matid>

<sag>3.55947</sag>

</catenary>

</basegeometry>Ground Plane

The user can specify an infinite plane using the groundplane

primitive. Ground planes are currently always horizontal (i.e. their

normals point in the (+z) direction), though they can be rotated

(with care) by using the instance transformation.

Default

The default ground plane is located with an anchor (pivot point)

at [0,0,0], but this can be changed with the addition of an <anchor>

element. The user must provide a material ID associated with the

plane, and also has the option of setting a temperature:

<basegeometry>

<groundplane>

<matid>100</matid>

<anchor><point><x>0</x><y>0</y><z>0</z></point></anchor>

<temperature>300</temperature>

</groundplane>

</basegeometry>|

|

The anchor point mostly exists to support defining the origin of a checkerboard in local space (see below). However, equivalent behavior for both the ground plane and the checkerboard can be produced by translating the instance of the plane. |

Checkerboard

The ground plane has the additional option of painting a checkerboard

on the surface. This is done by adding a checkers element to

description with an additional material ID and a width (in meters).

The checks start at the anchor point (x,y), so that can be used to

shift the pattern around.

<basegeometry>

<groundplane>

<matid>100</matid>

<anchor><point><x>0</x><y>0</y><z>0</z></point></anchor>

<checkers matid="101" width="1.0"/>

<temperature>300</temperature>

</groundplane>

</basegeometry>The user may also control the painting of individual checks using

an index system where the origin is the anchor point. Note that the

material ID of either the plane or the checks may be 0 to be

transparent and that indices may be negative.

<basegeometry>

<groundplane>

<matid>100</matid>

<anchor><point><x>0</x><y>0</y><z>0</z></point></anchor>

<checkers matid="100" width="1.5">

<paint xindex="0" yindex="0" matid="101"/>

<paint xindex="1" yindex="1" matid="101"/>

</checkers>

<temperature>300</temperature>

</groundplane>

</basegeometry>Sphere

The sphere description allows the user to set the center of the sphere, a radius, the material ID and temperature of the object.

<basegeometry>

<sphere>

<matid>100</matid>

<center><point><x>0</x><y>0</y><z>0.5</z></point></center>

<radius>0.8</radius>

<temperature>300</temperature>

</sphere>

</basegeometry>Texture coordinates

This primitive has a built-in UV coordinate system that is computed as:

\begin{eqnarray} u &=& \phi / ( 2\pi ) \nonumber \\ v &=& (\pi - \theta ) / \pi \nonumber \end{eqnarray}

which are based on the azimuth and zenith angles of the hit (relative to the sphere), respectively.

Secchi Disk

A Secchi disk is a high contrast target often used for measuring

turbidity in natural waters. DIRSIG provides an easy way to set

this up by providing a disk that accepts two materials as input,

but is otherwise the same as the disk previously described:

<basegeometry>

<secchidisk >

<matid_a>100</matid_a>

<matid_b>101</matid_b>

<radius>1</radius>

</secchidisk>

</basegeometry>Sinusoids

The sinusoid primitive allows the user to create an analytical sinusoidal surface constrained to a box. The sinusoid itself need not be aligned with the box — a 2D orientation can be provided, as well as the period and a phase shift.

Texture coordinates

This primitive has a built-in UV coordinate system that is aligned with the orientation of the wave. The U coordinate repeates with every wave cycle (linearly increasing with the projected horizontal distance and not linear along the surface) and the V coordinate is orthogonal to the wave orientation.

Surface

If the box height is equal to twice the magnitude of the sinusoid, then the object created is a surface:

<basegeometry>

<sinusoid>

<matid>100</matid>

<lowerextent><point><x>-1.0</x><y>-1</y><z>0.0</z></point></lowerextent>

<upperextent><point><x>1</x><y>1</y><z>0.2</z></point></upperextent>

<magnitude>0.1</magnitude>

<orientation><vector><x>-0.8</x><y>0.4</y></vector></orientation>

<period>0.5</period>

<phaseshift>0.1</phaseshift>

</sinusoid>

</basegeometry>Solid

By defining a box that has a height greater than the peak to trough measurement of the sinusoid, the object becomes a solid — the same sinusoidal surface but with a box on the lower side:

<basegeometry>

<sinusoid>

<matid>100</matid>

<lowerextent><point><x>-1.0</x><y>-1</y><z>-0.4</z></point></lowerextent>

<upperextent><point><x>1</x><y>1</y><z>0.2</z></point></upperextent>

<magnitude>0.1</magnitude>

<orientation><vector><x>-0.8</x><y>0.4</y></vector></orientation>

<period>0.5</period>

<phaseshift>0.1</phaseshift>

</sinusoid>

</basegeometry>Regular Grid

A "regular grid" is a representation of a 3D voxelized field of a spatially varying volume. This data representation is useful for an object like a factory stack plume. The grid description is split between two different files:

-

The "grid" file, which indicates the number of spatial elements in each dimension of the grid and the properties of grid element, and

-

The inclusion in the GLIST file, which includes then name of the "grid" file and which specifies the spatial length of the grid elements (or "voxels") for each dimension.

|

|

The separation of the spatial length of grid elements from the the "grid file" allows a single grid to be used multiple times but with different scales. |

|

|

Because of the current configuration, a "Regular Grid" cannot be

instanced like other <basegeometry> at this time. To create

multiple instances of a single grid file, you should create multiple

<object> entries.

|

The following example shows the contents of a grid file:

142 142 64

43 57 0 206 795.444 1000.2030

44 57 0 206 795.228 1000.2030

41 58 0 206 795.228 1000.2030

... ... ... ... ... ...

... ... ... ... ... ...

... ... ... ... ... ...

The first line has three integers, denoting the dimensions of the grid. In

the example above, the grid is 142 x 142 x 64 boxes.

The remainder of the file consists of lines with six columns of data. The

first three columns indicate the voxel index (counting from 0). The fourth

column indicates a DIRSIG material ID corresponding to an entry in the

Material Database file (.mat). The fifth column indicates temperature in

Kelvin. The final column indicates concentration in parts per million

(ppm).

|

|

Specifying voxel data for each grid voxel is not required. Unspecified voxels are treated as being empty. Furthermore, empty voxels do not take up memory, though they do slow the ray-tracing process to some degree. |

The "grid" file is then inserted into the scene via a GLIST entry like the one shown below:

<basegeometry>

<regulargrid>

<gridfilename>regular.grid</gridfilename>

<insertpoint>

<point><x>10</x><y>10</y><z>0</z></point>

</insertpoint>

<voxeldeltax>1.0</voxeldeltax>

<voxeldeltay>1.0</voxeldeltay>

<voxeldeltaz>0.5</voxeldeltaz>

</regulargrid>

</basegeometry>The <insertpoint> indicates the Scene ENU coordinates (in meters) to

insert the origin of the grid (the 0,0,0 coordinate of grid).

The parameters <voxeldeltax>, <voxeldeltay> and <voxeldeltaz>,

associate a physical size to respective XYZ dimensions of the voxels.

When information in the grid file and the GLIST specification are combined:

-

The grid contains 142 x 142 x 64 grid elements (from the "grid" file)

-

The grid is 142m x 142m x 32m (using the voxel sizes from the GLIST file)

-

The origin of grid is at

10, 10, 0in the Scene ENU coordinate system (from the GLIST file).

Height Fields

|

|

The heightfield geometry object is only available in DIRSIG4. The wave spectrum portion of the model is available as one of the medium interface plugins (WaveSpectrum documentation). |

A <heightfield> is a 3D representation of a (potentially dynamic)

2D array of height data. It is used in conjunction with a

<heightmodel> that defines the heights at

each sample point. The model can be as simple as an image (mimicking

an unoptimized conversion of elevation data to facetized geometry)

or as complex as a wind-driven wave surface that develops over time.

The options to the height field itself are fairly limited:

<basegeometry>

<heightfield>

<matid>100</matid>

<boxmode>false</boxmode>

<cachesize>100</cachesize>

<heightmodel type="...">

...

</heightmodel>

</heightfield>

</basegeometry>where <matid> defines the material assigned to the surface (which

may be mapped as with other surfaces — the uv space is defined for

the horizontal extents of the box height field, with the minimum

horizontal point corresponding to the minimum uv point). The two

other inputs (<boxmode> and <cachesize>) are optional and rarely

used. The <boxmode> uses boxes to model the surface rather than

facets. The <cachesize> dictates the maximum number of instantiations

of a surface that are held in memory to optimize non-sequential

intersection of dynamic surfaces (in particular, this enables faster

per-pixel temporal integration). The default values for the two

optional parameters are "false" and "100", respectively.

The height field is primarily a way to facilitate bringing regularly sampled height data into DIRSIG without going through an intermediate step of transforming the height data into a facetized 3D object. The advantage of the height field is that all ray tracing is done directly on the height field data itself using an optimized grid traversal algorithm, usually saving both memory and some run time for intersections. This is convenient for static height fields (e.g. terrain) and a necessity for dynamic height fields (e.g. waves)

Internally, the height field is just the grid of data points, with individual surfaces that connect each set of four neighboring points being generated on the fly. This can be seen in a low resolution render using the "box mode", which uses a 3D box at the base of the height field extended to the maximum height of the four neighboring points:

Box mode is only useful under very limited circumstances beyond visualization and normally we want to use the height field in the (default) facetized mode. In this mode, the box is replaced by two triangular facets which collectively have vertices at each of the 4 neighboring data points:

To generate physically realistic scene geometry, the resolution of the grid should be high enough so that the facetization is significantly sub pixel, e.g.

The facetized height field can be treated just like any other facetized piece of geometry — it can be assigned maps and can be given reflectance and transmittance properties:

See the height model documentation for details on how to drive the underlying data.

Base Sources

A <basesource> is analogous to a <basegeometry> element and

supplies the definition of a single source that can be instanced

multiple times. Its availability in the GLIST provides an alternative

to the GDB (Geometric Database) based definition of

a point source using a piece of geometry (see Sources)

and allows for adding new types of sources in the future. Currently,

the only type of base source available is a point source.

Point Source

Using a <pointsource> element as the base source in the GLIST

provides the same functionality as the point sources described in

Sources without requiring a piece of geometry

to define the position, direction and associated material ID.

Instead, each point source defined as a base source is always located

at the scene origin (it can then be re-positioned using the

translation). The default pointing direction is in the positive Z

direction, but this can be overridden by rotating an instance or

providing an optional new default pointing vector. An element

attribute provides the associated material ID and is mandatory:

<basesource>

<pointsource matid="777">

<pointing><vector><x>0.0</x><y>0.0</y><z>-1.0</z></vector></pointing>

</pointsource>

</basesource>|

|

Scaling a point source in the instance has no effect! |

Instances

Instancing is technique that has been used in the computer graphics community for a long time to assist in making large scenes using a smaller number of "base" objects. Each "instance" is internally represented by a lightweight object referencing a "base" object and a set of translation, rotation and scaling operations to be applied to the object. The key is that the "base" geometry does not need to be duplicated for each instance, because the translation, rotation and scaling can be quickly applied to each ray intersecting the instance rather than to base geometry.

Note that the instancing transform makes several assumptions about the base geometry provided for each object:

-

The translation of the base object is applied to the origin of the object.

-

The rotation of the base object is also relative to the origin of the object.

If the object is not "centered" in the described fashion, the rotation of the object may yield unexpected results.

|

|

In most cases, it is desired that the user modify the object geometry so that the model is centered about the X and Y origin and the bottom of the model (smallest Z value) is at the Z origin. In this configuration, it is very easy to place the object within the scene. |

An instance can also be named, which is useful when other sections of the glist need to refer to it (such as the anchoring mechanism in some of the random fills). The name is provided by a "name" attribute and should be unique (which also means that it needs to be at the highest level of embedded instancing).

Static Instances

A "static" instance places the base geometry at a specific location and orientation with the specified scaling. There are currently two ways to define a static instance:

-

XYZ Axis Triplets

-

4x4 Transform Matrix

XYZ Axis Triplets

The order of operations is:

-

The object is scaled

-

Then, the object is rotated

-

Finally, the object is translated

The explicit translation, scale and rotation values supplied here are used internally to form the affine transform used by DIRSIG to describe the instance.

|

|

The order of the rotations affects the final orientation of the object. |

|

|

A scale of 0 is considered invalid.

|

The following is an example of inserting an instance of an object using the "Scene ENU" coordinate system:

<staticinstance>

<translation>

<point><x>-20</x><y>-55</y><z>10</z></point>

</translation>

<rotation units="degrees" rotationorder="xyz">

<cartesiantriple><x>30</x><y>0</y><z>60</z></cartesiantriple>

</rotation>

<scale>

<cartesiantriple><x>1</x><y>1</y><z>10</z></cartesiantriple>

</scale>

</staticinstance>The <cartesiantriple> elements specify the quantities for the respective

XYZ dimensions. The units attribute in the <rotation> element

specifies the units of the angles in the associated <cartesiantriple>.

The rotationorder attribute in the <rotation> element specifies the

order that the rotations are performed in.

For example, xyz implies the objects rotated about the X axis, then the

Y axis and finally the Z axis.

The GLIST file also supports geolocation of objects. The following is an example using the "Geodetic (Lat/Long/Alt)" coordinate system to specify the location:

<staticinstance>

<translation>

<geodeticlocation>

<latitude>43.120</latitude>

<longitude>-78.450</longitude>

<altitude>300.000</altitude>

</geodeticlocation>

</translation>

<rotation units="radians" rotationorder="zyx">

<cartesiantriple><x>0</x><y>0</y><z>0.78539816</z></cartesiantriple>

</rotation>

<scale>

<cartesiantriple><x>1</x><y>1</y><z>1</z></cartesiantriple>

</scale>

</staticinstance>Note that in this example the <rotation> has units of radians and

the rotation order is ZYX.

|

|

In DIRSIG 4.5.0, the new <location> format was introduced to

simplify the older <scenelocation>, <geodeticlocation>,

<utmlocation> and <eceflocation> format. Consult the

Coordinate Systems document for the XML

schema for these coordinate systems.

|

|

|

If one or more of the three affine transformation components are missing, DIRSIG will not do anything to the original geometry for that particular component (e.g. a missing translation tag means that no additional translation will be added, though rotation and scaling may be applied if they are present). |

If the user wants to use the base geometry without any transformations at all they can use the brief syntax:

<staticinstance/>to indicate that object maintains its original position, rotation and scaling.

4x4 Affine Transform

The second option available is to specify the instance via a 4x4

affine transform matrix. The transform is provided

via the <matrix> element within the <staticinstance>. The matrix

needs to be provided in row-major

order as a comma separated list:

<staticinstance>

<matrix>+2, 0, 0, -5, 0, +2, 0, -5, 0, 0, 2, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1</matrix>

</staticinstance>Binary Affine Transforms

In 2024, an external, binary static instance transform file option was introduced. The purpose of this option was to streamline the description of scenes containing a large number (millions) of static instances. When using the conventional methods described above, the size of the GLIST files would rapidly grow due to the overhead of the XML markup required to describe an instance. This resulted in massive GLIST files and very slow parsing times when the file was read in by the scene compiler. The solution was to introduce a binary file that could store a large number of static instances. Use of this binary file option dramatically reduces the overall scene file size and time to compile the scene.

The format of the binary file is simple. The file starts with a

single, unsigned 32-bit integer (uint32) containing the number

of instances in the file. The remainder of the file is the static

instances stored as 4 x 3 affine transforms (the

last row of the 4 x 4 affine transform matrix always contains 0,

0, 0, 1, so it is eliminated to reduce space) blocks in

row-major order using

single-precision, floating-point (float32) values.

| Name | Offset (bytes) | Data Type |

|---|---|---|

Number of instances |

0 |

uint32 |

Instance #1 |

4 |

12 x float32 |

Instance #2 |

52 |

12 x float32 |

… |

… |

… |

Instance #N |

4 + (Nx12x4) |

12 x float32 |

A binary instance data file is used with an object via the

<staticinstancebinaryfile> tag:

<object>

<basegeometry>

<obj><filename>objects/tree.obj</filename></obj>

</basegeometry>

<staticinstancebinaryfile>lists/trees.instances</staticinstancebinaryfile>

</object>The binary static instance file option also supports automatic

"anchoring", where the user provides the name (tag) of another

object’s instance(s) that will be used to recompute the Z location

of each instance in the file. The user can also enable automatic

rotation, where each instance is rotated to align the instance’s

up axis (+Z) with the normal of the anchoring surface at that XY

location. These options are accessed as attributes to the

<staticinstancebinaryfile> element as shown below:

<object>

<basegeometry>

<obj><filename>objects/ground.obj</filename></obj>

</basegeometry>

<staticinstance tags="ground"/>

<object>

<object>

<basegeometry>

<obj><filename>objects/car.obj</filename></obj>

</basegeometry>

<staticinstancebinaryfile anchor="ground" anchorrotation="true" tags="cars">lists/car.instances</staticinstancebinaryfile>

</object>|

|

The tags will be applied to all the instances contained in the file.

|

Dynamic Instances

Delta (Keyframe) Motion

An object can be dynamically positioned as a function of time using an external Delta Movement (sometimes referred to as "keyframe" movement) file:

<dynamicinstance>

<motion type="delta">

<filename>truck.mov</filename>

</motion>

</dynamicinstance>This model is explained more in the DeltaMotion1 demo.

Generic Motion

An object can be dynamically positioned as a function of time using an external Generic Platform Position Data file:

<dynamicinstance>

<motion type="generic">

<filename>truck.ppd</filename>

</motion>

</dynamicinstance>With DIRSIG5, this motion model includes a similar start/end "hidden"

option that is available in the DeltaMotion

model. This is enabled with the optional <options> element inside the

<motion> element:

<dynamicinstance>

<motion type="generic">

<options starthidden="true" endhidden="true"/>

<filename>$SCENE_DIR/geometry/sedan_red_subaru.ppd</filename>

</motion>

</dynamicinstance>The starthidden and endhidden attributes in the <options> element

control the respective start and end hidden flags for the instance the

motion model is associated with.

|

|

The default behavior is that the instance does not start or end

"hidden". To enable the hidden flags, the <options> element

must be introduced.

|

This model is explained more in the GenericMotion1 demo.

Flexible Motion

An object can be dynamically positioned and oriented as a function of time using the Flexible Motion model:

<dynamicinstance>

<motion type="flexible">

<locationengine type=... >

...

</locationengine>

<orientationengine type=... >

...

</orientationengine>

</motion>

</dynamicinstance>This model is explained more in the FlexibleMotion1 demo.

Turning Instances On/Off (Time Windows)

The enabled attribute has been used in some of the previous examples to turn objects and included files on or off in the glist file. The instances themselves don’t have an equivalent input, but it is possible to schedule when they are part of the scene by providing a timewindow attribute,

<staticinstance timewindow="...">

...

</staticinstance>The time window is a generic term for an on/off schedule and the inputs are dependent on the schedule being used. The type of schedule is automatically determined (the attribute is always timewindow).

Time Window: Simple

The simple time window is defined by

<staticinstance timewindow="[a:b]">...</staticinstance>where a and b correspond to the time the instance will be "turned on" and "turned off," respectively. They are both given in decimal seconds from the start of the simulation.

Time Window: Daily

The daily time window is similar to the simple time window, but it repeats every day. Instead of providing times from the start of the simulation, the inputs to this window are two (local) clock times and are not dependent on the simulation start,

<staticinstance timewindow="[HH:MM:SS.S,HH:MM:SS.S]">...</staticinstance>As with the simple format, seconds can be provided as decimal values. The hours component uses a 24hr clock.

Including other Geometry Lists

Although you can use another GLIST/ODB as the base geometry and then instance it, you can also "include" an external GLIST and ODB files. The following is an example of including an external GLIST file:

<geometrylistinclude name="Cars" enabled="true">cars.glist</geometrylistinclude>This option allows you to break a larger scene down into smaller parts. For example, the MegaScene1 scene was split up based on the names of roads in the real-world scene:

<geometrylist enabled="true">

<geometrylistinclude name="Belmeade_Rd" enabled="true">tile_1/Belmeade_Rd.odb</geometrylistinclude>

<geometrylistinclude name="Biltmore_Dr" enabled="true">tile_1/Biltmore_Dr.odb</geometrylistinclude>

<geometrylistinclude name="Briarwood_Dr" enabled="true">tile_1/Briarwood_Dr.odb</geometrylistinclude>

<geometrylistinclude name="Bristol-Winona-StPaul" enabled="true">tile_1/Bristol-Winona-StPaul.odb</geometrylistinclude>

<geometrylistinclude name="Cambria_Rd" enabled="true">tile_1/Cambria_Rd.odb</geometrylistinclude>

<geometrylistinclude name="Chimayo_Rd" enabled="true">tile_1/Chimayo_Rd.odb</geometrylistinclude>

<geometrylistinclude name="CircleCourt" enabled="true">tile_1/CircleCourt.odb</geometrylistinclude>

...

</geometrylist>Tangent Data

|

|

This feature can be used with OBJ, FBX, and Assimp base geometry. It is not supported for GDB. |

For some advanced, physics-based rendering (PBR) methods, the calculations require an explicit and unambiguous orientation context across surfaces. This is frequently captured as 3x3 matrix using the tangent, bi-tangent, and normal (TBN) direction values. By default, the DIRSIG scene compiler does not generate and store this data in the scene data model used at run time as it increases the storage requirements and is not used by most of the materials in DIRSIG. However, some map types (i.e., normal maps) and reflectance models (anisotropic BRDFs) can utilize this data.

The scene compiler can optionally include the

tangent data in the scene data model for use by surface properties

that support explicit orientation. To generate this data, add the

generatetangents attribute to the <obj>, <fbx> and/or <assimp>

element and set it to "true":

<basegeometry>

<obj generatetangents="true">

<filename>objects/tree.obj</filename>

</obj>

</basegeometry>|

|

The scene data model does not store a complete TBN matrix when this option is requested. The normal vector is already explicitly captured and this option adds the tangent vector. The bi-tangent (B vector) is assumed to be orthogonal to the normal and tangent. |

Material Overrides

|

|

This feature can be used with GDB, OBJ, FBX, and Assimp base geometry. |

Sometimes facetized objects produced by other creators (perhaps purchased and/or downloaded from various online sources) contain a larger number of materials than you wish to use in DIRSIG. For example, we have seen cases where a creator defined unique materials for common geometric components within a single object (e.g., "front_left_tire", "front_right_tire", etc.) that you intend to model with a single material (e.g., "tire"). To address this, one option is to load the asset into a 3D content editing tool and change these material assignments. However, the GLIST file provides a simpler method in the form of mechanism for performing material overrides at either the object or instance level.

Object-Level Overrides

Material overrides can be made at the object level inside the

<gdb>, <obj>, <fbx>, etc. factized geometry elements within

the <basegeometry> element:

<basegeometry>

<obj>

<filename>vw_golf.obj</filename>

<assign id="blue_paint">default</assign>

<assign id="tire">front_left_tire</assign>

<assign id="tire">front_right_tire</assign>

<assign id="tire">rear_left_tire</assign>

<assign id="tire">rear_right_tire</assign>

<assign id="chrome">front_bumper</assign>

<assign id="chrome">rear_bumper</assign>

<assign id="glass">windshield</assign>

</obj>

</basegeometry>With the exception of the first entry, each assignment is done by

remapping the material name (e.g. "front_left_tire") used in the

geometry file (in this case, an OBJ file using the usemtl tag) to

an alphanumeric material label (ID) in the DIRSIG

material database used for this object.

|

|

If using an older DIRSIG material database using only numerical

material IDs, the optional name attribute can be added to each

<assign> element to indicate the DIRSIG material being used.

This attribute is purely for user documentation purposes.

|

|

|

To get a list of material names used in a facet geometry file, you can use the DIRSIG object_tool utility. |

The first entry above is a special assignment. If the material name

from the geometry file is "default" then DIRSIG will assign any

unknown (i.e unassigned) material to the associated label (ID). In

this case there are a large number of "paint" materials associated

with the vehicle geometry corresponding to different parts of the

body. Rather than list them all individually, we just have the

default assignment take care of assigning them all to the paint

material.

|

|

The "default" assignment is also useful for making sure that all materials in the OBJ file are assigned to a valid ID. Otherwise, if the list of assignments is missing just a single invalid material the whole geometry will fail to load. |

Instance-Level Overrides

The example above illustrates performing the material override on

the base geometry (GDB, OBJ, FBX, etc.). When this method is used

all of the instances of that geometry will share those overrides.

However, overrides can also be performed on a per instance basis

as well. For example, you might have a car OBJ that has a specific

material for the body paint and you want to use that OBJ to instance

multiple versions of that car with each instance having a unique

body paint. To achieve this, the same <assign> mechanism can be

used within a <staticinstance> or <dynamicinstance>:

<basegeometry>

<obj>

<filename>vw_golf.obj</filename>

<assign id="body_paint">default</assign>

<assign id="tire">front_left_tire</assign>

<assign id="tire">front_right_tire</assign>

<assign id="tire">rear_left_tire</assign>

<assign id="tire">rear_right_tire</assign>

<assign id="chrome">front_bumper</assign>

<assign id="chrome">rear_bumper</assign>

<assign id="glass">windshield</assign>

</obj>

</basegeometry>

<staticinstance name="parked_vw_golf">

<assign id="blue_paint">body_paint</assign>

<translation>

<point><x>-20</x><y>-55</y><z>0</z></point>

</translation>

</staticinstance>

<dynamicinstance name="driving_vw_golf">

<assign id="green_paint">body_paint</assign>

<motion type="delta">

<filename>motion/driving.mov</filename>

</motion>

</dynamicinstance>In this example, a series of overrides are made at the object-level

(inside the <obj> element and then each of the two instances make

an instance-level overrides of the body_paint material with

blue_paint and green_paint, respectively.

|

|

Instance-level material overrides are applied after the object-level overrides. |

Sub-Object Attribution and Motion

|

|

This feature can be used with GDB and OBJ base geometry. |

The GLIST file also provides a way for the user to assign materials

and motion to "parts" within a facetized object. A "part" is an

explicit grouping of facets in a GDB (a PART) or

OBJ (facets within a "g" group). This is achieved

via the optional <properties> element within the base geometry

type element. Below is an example from the

SubObjectMotion2 demo,

where every polygon on the helicopter is initialially assigned a

single DIRSIG material (i.e., gray_paint) via the

material override mechanism. Inside

the <properties> element, the <matid> element overrides that

default gray_paint material with a DIRSIG material with the label

(ID) of "blades" to a part named "BLADES" (corresponding to the

facets associated with the rotor blades). In addition, the blades

are assigned a FlexMotion "spin" setup

that introduces rotation to the rotor blades around the Z axis (see

axis="0,0,1"). The <origin> specifies the local origin for the

part that the motion should be applied to. In this case,

0, 0, 6.734 correspondes to the base of the rotor blade hub.

<obj>

<filename>helicopter.obj</filename>

<assign id="gray_paint">default</assign>

<properties>

<origin>

<part name="BLADES" enabled="true">

<matid>rotor</matid>

<origin><x>0</x><y>0</y><z>6.374</z></origin>

<motion type="flexible">

<locationengine type="fixed">

<location frame="scene">

<x>0.0</x><y>0.0</y><z>0</z>

</location>

</locationengine>

<orientationengine type="spin">

<data source="internal" datetime="relative" frame="scene" delimiter="," axis="0,0,1">

<![CDATA[

0,0

10.0,314.15

]]>

</data>

</orientationengine>

</motion>

</part>

</properties>

</obj>|

|

The enabled attribute for any <part> can be set to false to

disable a given part (make it disappear).

|

|

|

In DIRSIG4, the <properties> element appeared at a different

level in the XML schema. In DIRSIG4, it was inside the

<object> element rather than inside the <gdb>,

<obj>, etc. element. This old position in the XML

will not be recognized by the DIRSIG5

scene2hdf scene compiler.

|

<properties> element.<object>

<basegeometry>

<obj>

<filename>helicopter.obj</filename>

<assign id="gray_paint">default</assign>

</object>

</basegeometry>

<properties>

<matid>rotor</matid>

...

</properties>

...

</object>Population based variants

When populating a scene with geometry, we often have a situation where we want many variations of a class of object (e.g. many vehicle geometries with different paint colors, or suburban house geometries with varying building materials) that are interchangeable. In other words, all that matters is that an object of a particular type go in a specific spot, the specific object used is irrelevant. If, say, there are a 100 different vehicle variants within a population (potentially with a known distribution within that population) it would be nice to have a single list of where those vehicles should go and have DIRSIG automatically assign one of the variants (following the distribution) to each of those instances.

Using the basic glist tools, developing a population of instances means having to use copies of the same geometry that vary only by the material ids (to represent different material variants in the population) and separate lists of instances for each object. Not only is this tedious and messy (even with the help of external scripts), but we also end up creating redundant geometry (i.e. each material variant of an object replicates the same base geometry) and a complex set of glist files that are difficult to modify. As an alternative, DIRSIG provides a number of built-in tools to help input populations of objects, automatically varying the geometry used and the materials assigned based on user-provided inputs. Geometric and material variants are described in more detail below.

Adding geometry variants

Adding more than one <basegeometry> entry to an object allows the

user to specify a pool of objects that will be randomly selected

from for each instance in the instance list. The different "base

geometry" objects can be

weighted to create a discrete population distribution that reflects different proportions. The user must still provide a list of instances (either static or

dynamic) but the model will choose which "base geometry" is used

with each instance based on the weightings. This mechanism can be

used for a variety of applications, including:

-

Quickly populate a forest (the user supplies tree locations as static instances) so that the final forest reflects the supplied proportions of each tree species (provided as the set of "base geometry" objects).

-

Quickly populate a traffic pattern (the user supplies the vehicle tracks as dynamic instances) with many different types of cars. If a car of a certain make or type is more or less common, the base geometry weightings can be manipulated to reflect this.

The different base geometries are defined by creating multiple

<basegeometry> elements within an <object> element. Consider

the following example from a glist file:

<geometrylist>

<object>

<basegeometry weight="1">

<glist><filename>cars/vw_beetle.glist</filename></glist>

</basegeometry>

<basegeometry weight="2">

<glist><filename>cars/generic_pickup.glist</filename></glist>

</basegeometry>

<basegeometry weight="2">

<glist><filename>cars/generic_suv.glist</filename></glist>

</basegeometry>

<basegeometry weight="2">

<glist><filename>cars/infiniti_g35.glist</filename></glist>

</basegeometry>

...

</object>

</geometrylist>The weight attribute is used to manipulate the relative proportion

of that base geometry in the overall population.

|

|

If the weight attribute is not included, the default weight is 1.

|

|

|

The base geometry weight values are summed and normalized to

produce the relative fractions of each base geometry in the

overall population.

|

In this example, we have defined a pool of four different cars that will

be randomly selected from as each instance is defined. Note that the

various weight values in this case have the Volkswagen Beetle

(vw_beetle.glist) appearing less often than the other vehicles in the

scene. It is important to realize that since the vw_beetle.glist

file (and the other 3 vehicle GLIST files) include randomized material

attributions (discussed in the next section) that each instance

will get a random base geometry (which vehicle type) and a random

attribution of that base geometry (the paint type on that vehicle).

|

|

To add another base geometry to the pool, the user just needs to

add another <basegeometry> to the <object> section.

|

Adding material variants

The ability to randomly reassign material properties to each instance

is performed via a <population> element within an <object>

element (separate from the <basegeometry> element(s). A

<materialvariant> element defines which original material ID will

be reassigned and the weighted distribution of assignable material

IDs.

In the example below, the model looks for surfaces attributed with material

ID #500 (the default material ID for a car, which is associated

with the body of the vehicle). These surfaces will be reassigned either

material ID #501, #502, #503,#504 or #505 based on the respective weight

for each ID. In this case, these material IDs correspond to different vehicle

body paints in the DIRSIG material database:

<geometrylist>

<object>

<basegeometry>

<obj>

<filename>Cars/vw_beetle.obj</filename>

<assign name="paint" id="500">default</assign>

...

</obj>

</basegeometry>

<population>

<materialvariant>

<variantid>500</variantid>

<seed>1234</seed>

<distribution>

<matid weight="2">501</matid>

<matid weight="1">502</matid>

<matid weight="1">503</matid>

<matid weight="1">504</matid>

<matid weight="2">505</matid>

</distribution>

</materialvariant>

</population>|

|

If the weight attribute is not include, the default weight is 1.

|

|

|

The seed is optional — if not provided, the global random number generator is used instead. |

|

|

The material ID weight values are summed and normalized to

produce the relative fractions of material ID in the overall

population.

|

In this case, material ID #501 and #505 have larger weights than the other

materials, reflecting that these body colors are more likely to be chosen.

The weights add up to 9, which means #501 and #505 will be assigned to

2/9ths (each) of the vehicles and the remaining materials will be assigned

to 1/9th (each) of the vehicles.

|

|

To reassign another material ID, the user just needs to add

another <materialvariant> element within the <population>

element.

|

|

|

Using the same seed for multiple material variants will make sure that the same combinations of material are used with every random draw. |

Including lists of instances

The locations of objects within the scene are often driven by a third-party tool or script that generates position information, but not a full glist. If that data is in the form of static/dynamic instance entries, it would be nice to directly use that information without having to manually wrap it with a (potentially nontrivial) set of object definitions.

For example, we might setup a generic population of building models in a glist (different geometric models and material variants), but have a third party tool (such as a procedural scene builder) tell us where those buildings should go and how they are oriented. We could have that tool generate a list of instances (or convert its native output to DIRSIG instances) and then manually copy/paste the building object information in, but this becomes tedious if future modifications of the instance list is necessary. Instead, it would be a lot handier to have DIRSIG grab the contents of one file (the list of instances) and insert it in the current file (the glist with the building population). That way the glist never needs to be modified if we are changing the positions and any modifications to the included file will be used automatically.

To support this, DIRSIG has minimal support for the XInclude (XML

Inclusions) standard via an xi:include embedded in the XML file. When

this tag is encountered, the included file is loaded, converted to an

XML fragment, and inserted into the current XML tree being read in. To

read in a list of instances for example, you’d use:

<object>

...

<xi:include href="instances.list"/>

</object>where "instances.list" is a text file in the same directory consisting of (bare) XML instance entries.

|

|

DIRSIG does not support any other options/attributes of the XML

Inclusion standard and only minimally supports href

(parse="text" is assumed). This may change in the future

(hopefully with native Qt support) which is why the syntax

is used.

|

Random fills

In addition to explicitly defining where objects go within the scene, it is possible to have DIRSIG automatically fill a region (usually randomly) with instances of one or more types of objects. Traditionally, this sort of approach has been done by writing external scripts to generate instancing information (potentially using truth images generated from DIRSIG). While this is still an effective technique, the integrated tools in DIRSIG allow the instance generation to robustly place objects, checking for overlaps with existing scene geometry or anchoring based on a subset of the scene.

|

|

While it is possible to instance a geometry list containing a random fill, you will always get the original, filled geometry and the content of the copies will match the original (i.e. they will not be independently filled). This is generally only useful for quickly generating cyclic boundary conditions. The random fills are intended to be unique components of a scene. |

The instance generators defined here are all defined within a

<randomfill> tag and only one generator can be defined per tag (though

its possible to use multiple <randomfill> tags). The <randomfill>

element has two optional attributes that can be used to save out the

location of instances and then use them if the save file exists, e.g.:

<randomfill savefile="instances.sav" loadinstances="true">

...

</randomfill>If the file "instances.sav" doesn’t exist then the random fill will generate instances based on the fill mechanism (see below) and will save out the instance entries to the file. If the file does exist then the instances will be read in (skipping any instance generation) if "loadinstances" is set to "true". If it is false (or absent) then the existing file is overwritten (if no "savefile" exists then nothing is loaded or saved). Attempting to load a nonexistent save file (i.e. "loadinstances" set to "true") will result in an error.

|

|

The save mechanism is very useful to make sure that any subsequent runs use the exact same distribution of objects in the scene. It also might save a bit of time during initialization if the random fill is very large or complicated. |

|

|

The fill tools are still prototypes at this time and the exact syntax is subject to change |

The anchor list

The simplest form of random fill is based on reading in a list of horizontal positions within the scene and automatically filling them with geometry objects taken from a defined population (see previous discussion of geometry and material variants). For example, we could setup a small fleet of cars (different geometry models with material variants) that looks like this:

<object enabled="true">

<basegeometry weight="1">

<glist><filename>vw_beetle.glist</filename></glist>

</basegeometry>

<basegeometry weight="2">

<glist><filename>infiniti_g35.glist</filename></glist>

</basegeometry>

<basegeometry weight="1">

<glist><filename>generic_pickup.glist</filename></glist>

</basegeometry>

<basegeometry weight="1">

<glist><filename>toyota_corolla.glist</filename></glist>

</basegeometry>

<basegeometry weight="1">

<glist><filename>vw_golf.glist</filename></glist>

</basegeometry>

<basegeometry weight="1">

<glist><filename>nissan_fairlady.glist</filename></glist>

</basegeometry>

<basegeometry weight="2">

<glist><filename>bmw_x5.glist</filename></glist>

</basegeometry>

<population>

<materialvariant>

<variantid>500</variantid>

<distribution>

<matid weight="2">501</matid>

<matid weight="1">502</matid>

<matid weight="1">503</matid>

<matid weight="1">504</matid>

<matid weight="2">505</matid>

<matid weight="2">506</matid>

<matid weight="2">507</matid>

</distribution>

</materialvariant>

</population>

...

</object>Now we can use the new instancing tool to fill the spots listed in one of our lists:

...

<randomfill loadinstances="false" savefile="instances.sav">

<anchorlist>

<filename>drivewayspots.txt</filename>

<blocking>blocking.txt</blocking>

<fillpercent>80</fillpercent>

<reversepercent>30</reversepercent>

<anchor>lot</anchor>

<seed>33932194</seed>

<posdev><point><x>0.02</x><y>0.4</y><z>0</z></point></posdev>

<rotdev units="degrees"><point><x>0</x><y>0</y><z>3</z></point></rotdev>

</anchorlist>

</randomfill>

</object>where the options are:

filename-

name of the file with the location information (rows of <x> <y> <dx> <dy> where <x> and <y> are the horizontal position coordinates in the local ENU coordinate system and <dx> <dy> are the "facing" orientation of the spot)

blocking-

optional name of another file that blocks placement of objects (rows of <x> <y> <wx> <wy>, where <wx> and <wy> are the axis aligned widths of the block — this is useful for excluding areas externally, such as making sure light posts aren’t placed in driveways)

fillpercent-

the percent of locations that will be filled (randomly)

reversepercent-

the percent of placements that will point in the opposite direction from that given (useful for parking spots where cars can point in two directions)

anchor-

the instance of geometry on which the object should be placed (corresponds to the name attribute of an instance)

minscaleandmaxscale-

the minimum and maximum random uniform scaling factor to be added to each instance. The default for both variables is

1(no scaling). seed-

the specific seed to use for random draws (can be changed to vary placement without modifying the run-time seed)

posdev-

a set of three (x,y,z) standard deviations for random offset (gaussian pull) from the given location

rotdev-

same as the position deviation, but for a rotation relative to the given direction (or the reversed direction if applicable); units are user-supplied as radians or degrees

An example of using this fill tool is shown below for a parking lot:

DIRSIG will supply the vertical position (and any slope-based rotation) automatically for the placed geometry based on the underlying terrain/object listed.

The density map

We often want to fill an area in the scene somewhat randomly (as opposed

to providing a list of locations), but want to have some control over the

spatial density of the distribution of objects. Additionally, if there

is stuff already in the scene, we potentially want to avoid planting

the new object on top of or intersecting those objects (for example,

we might want to add a distribution of trees around existing buildings

in the scene). The density map (<densitymap>) based random fill is

meant to handle these situations:

<randomfill>

<densitymap>

<count>50</count>

<mindist>0.1</mindist>

<maxdist>2.0</maxdist>

<matid>200</matid>

<minscale>0.5</minscale>

<maxscale>2.5</maxscale>

<anchor>lot</anchor>

<seed>33932194</seed>

<randomorientation>true</randomorientation>

</densitymap>

</randomfill>count-

number of objects (those listed in the same

<object>section) to try to place mindist-

the (approximate) minimum distance between placed objects at highest density [m]

maxdist-

the (approximate) maximum distance between placed objects at lowest (non-zero) density [m]

minscaleandmaxscale-

the minimum and maximum random uniform scaling factor to be added to each instance. The default for both variables is

1(no scaling). matid-

the material id associated with the density map to be used; if no density map exists, objects will be placed at random distances between the min and max; the material ID should also correspond to a material exiting in the anchor object being mapped to ensure that it is registered with the simulation

seed-

the specific seed to use for random draws (can be changed to vary placement without modifying the run-time seed)

randomorientation-

flag for having the placed object be rotated randomly (full 360 degree rotation)

As seen above, the <densitymap> fill takes a material ID associated

with a density map (defined in the maps section of the scene file). The

density map (defined in the scene file along with all other maps) might

look something like:

<maplist>

...

<!-- Parking density -->

<densitymap name="Parking Density Map" enabled="true">

<matidlist>

<matid>200</matid>

</matidlist>

<projector>

<uvprojector/>

</projector>

<image>

<filename>parking_density.png</filename>

</image>

</densitymap>

...

</maplist>The image used for the map is simply a grayscale image where the highest possible value (white) corresponds to the densest packing of objects and the lowest possible value (one digital count above black) corresponds to the least dense packing. A value of zero (absolute black) in the image means that no objects should be planted in that region (which is useful for masking out portions of the scene where objects would be planted otherwise).

The practical definition of density is based on the provided values for

<mindist> and <maxdist>. These values are approximately the spacing

between the placed object at the highest and lowest density, respectively

(they are actually the distances between the transformed bounding boxes

of the placed objects since it would be too expensive to test potentially

complex surfaces). When two objects exist in two different density regions

(e.g. two different points in a density gradient) then the distance

between them will be the average of the two density based distances.

|

|

If a density map (image) is not provided then the placement will pick a random spacing between the minimum and maximum distance |

|

|

Only the first valid density map for a surface will be used — it is not possible to define multiple density maps on the same surface currently (though the type of object can be varied uniformly using the population options) |

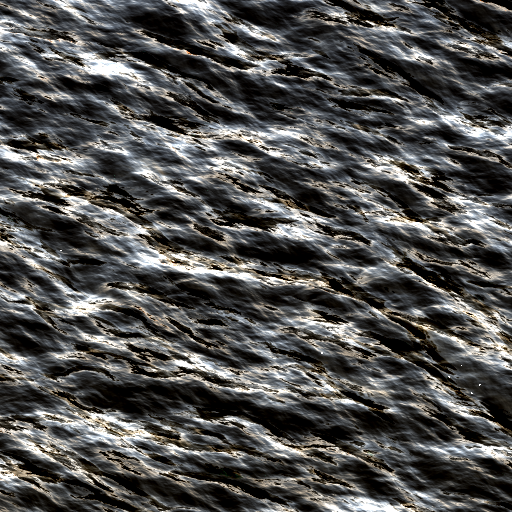

The following image is an example of using the density map to place stray shopping carts in a grocery parking lot scene in a semi-logical fashion (i.e. in between cars, and primarily between opposing stalls, but never in the drive aisles).

The density map we’re using (shown below, above the material map that defines the lines) shows how this was done. The area between opposing stalls has a band of pure white (highest density packing), the areas between cars have a darker value with a slight gradient (we want a few carts between vehicles, but make it very unlikely to pack two in close together), and finally the drive aisles are black, making sure there are no carts blocking traffic.

The other key part of the <densitymap> is the choice of <anchor>,

which is that name of a (unique) geometry instance in the scene. This the

object onto which the objects will be placed. If the anchor is occluded

by another object (e.g. a car on the parking lot when the lot is the

anchor), then the object won’t be placed. Otherwise each placed object

will rest on the anchor object based on its "origin" (usually set to

the center bottom of the object).

Note that our choice of anchor is important here (it was assigned to the parking lot geometry instance, "lot"). If the entire scene was used as the anchor then carts would be placed where ever they fell (though avoiding each other). The following image shows this (for a larger number of carts than used in the previous):

The <anchorlist> and <densitymap> fills are used in the Parking1

demo which was used to create the images shown here.

The polygon fill

The polygon (vertex) based fills are setup similarly to the density based fill except that objects are placed uniformly within each polygon:

<randomfill>

<polyfill>

<polyfile>yards/backyards.txt</polyfile>

<mincount>10</mincount>

<maxcount>40</maxcount>

<matid>910</matid>

<seed>42832</seed>

<randomorientation>true</randomorientation>

</polyfill>

</randomfill>with options:

polyfile-

The name of the file with the vertex information (rows of <x> <y>, where <x> and <y> are the horizontal position coordinates in the local ENU coordinate system; polygons are separated by two blank lines and the last vertex and first vertex should match for each polygon)

mincount-

The minimum number of objects to try to place within each polygon

maxcount-

The maximum number of objects to place within each polygon

matid-

The material id that objects can be planted on (e.g. the id corresponding to the lawn material)

minscaleandmaxscale-

the minimum and maximum random uniform scaling factor to be added to each instance. The default for both variables is

1(no scaling). seed-